The Founders' Vision

The number 435 is now synonymous with the U.S. House of Representatives. Yet, 435 is not enshrined anywhere the Constitution. The size of the House of Representatives is laid out in Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which mandates that representatives be apportioned among the states "according to their respective Numbers," a process to be guided by a decennial census.

The initial apportionment, prior to the first census, set the House size at a mere 65 members. However, the Framers intentionally did not set a static size for the House of Representatives. They fully expected the chamber to expand as the nation's population grew. In Federalist Paper No. 58, James Madison argued that the purpose of the census was to "readjust, from time to time, the apportionment of representatives" and to "augment the number of representatives" as the population increased. The size being set at 435 is nothing more than an historical artifact, a political compromise born from a decade of legislative paralysis and political infighting from the early 20th century.

Congress adhered to this founding principle for the first 13 apportionments. The House grew from 65 to 105 members following the inaugural census of 1790. This precedent of expansion was followed for every subsequent census until 1920. (There is one exception to this rule when the 1840 congress reduced the number of seats from 240 to 223.) As the nation's population swelled and new states were admitted to the Union, Congress passed successive apportionment acts that increased the total number of seats in the House. A state losing a seat meant a direct loss of power, prestige, and federal influence for its entire delegation. By simply expanding the chamber, Congress could accommodate population growth in some states without penalizing others. This century-long tradition established a powerful political expectation that reapportionment meant growth.

The Apportionment in the Early 20th Century

Following the 1910 Decennial Census, Congress set the size of the house to 433 with a single additional seat for Arizona and New Mexico upon their admission as states. So, as a result, in 1912, with AZ & NM gaining statehood, the size of the House was set to 435 members, with the average congressional district representing 210,000 people. This is the same time frame that the House removed desks for the individual members and added the bench seating that exists today because of space constraints.

The number 435 was not a special number with any significance. It was not derived from any constitutional source. It was the practical outcome under the Webster Method of Apportionment, also known as the Method of Major Fractions, while adhering to the tradition that existing states should not lose representation.

However, by the 1920 Census, America had undergone a massive demographic realignment. Between major events such as World War 1, the 1918 pandemic and other migration trends, America had become a majority urban country for the first time since her Founding. This shift of power from rural areas to urban areas led to a political earthquake in Congress.

Another outcome from this massive redistribution of population was that 60 new seats were required to maintain the tradition that states should not lose existing representation. Such a drastic increase in the size of the House combined with other political consequences led to Congress completely ignoring reapportionment for the remainder of the decade.

The Apportionment Crisis of the 1920s

By 1929, a compromise agreement was reached in the lead up to the 1930 Census. Former and incumbent legislators, governors, and academics all came together in creating the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 which had 2 important provisions.

1) Cap the size of the House at 435. Attempts to determine the “ideal size” were fraught and lead to heated debates. The act avoided the fight entirely by deciding to not find the “right” number but use the current number

2) Automate the Process - To prevent a repeat of the 1920s deadlock, the act created an automatic reapportionment mechanism. It required the President, after each census, to transmit to Congress a statement showing the population of each state and the number of representatives to which each state would be entitled This turn to an automated process represents a pivotal moment where legislators, unable to resolve an inherently political problem, effectively outsourced the decision making process to others.

Another important outcome from events of the 1920’s was the ultimate selection of a permanent apportionment method, or the mathematical formula behind the distribution of seats. These methods all included trade offs and were used like mathematical weapons for political maneuvering. Following the 1929 Permanent Apportionment Act, was the selection of , The Method of Equal Proportions: The Huntington-Hill Formula that has been used from each apportionment since 1940.

The 435-seat House of Representatives is not a number derived from constitutional wisdom or democratic theory. It is a historical accident, the legislative fossil of a political crisis that occurred a century ago. The decision to cap the House was a pragmatic compromise born from a decade of congressional gridlock, fueled by a profound demographic shift from a rural to an urban nation. The Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 was a solution not to the problem of representation, but to the problem of political paralysis. By freezing the number of seats at the then-existing 435 and automating the apportionment process, Congress abdicated one of its most fundamental and contentious responsibilities.

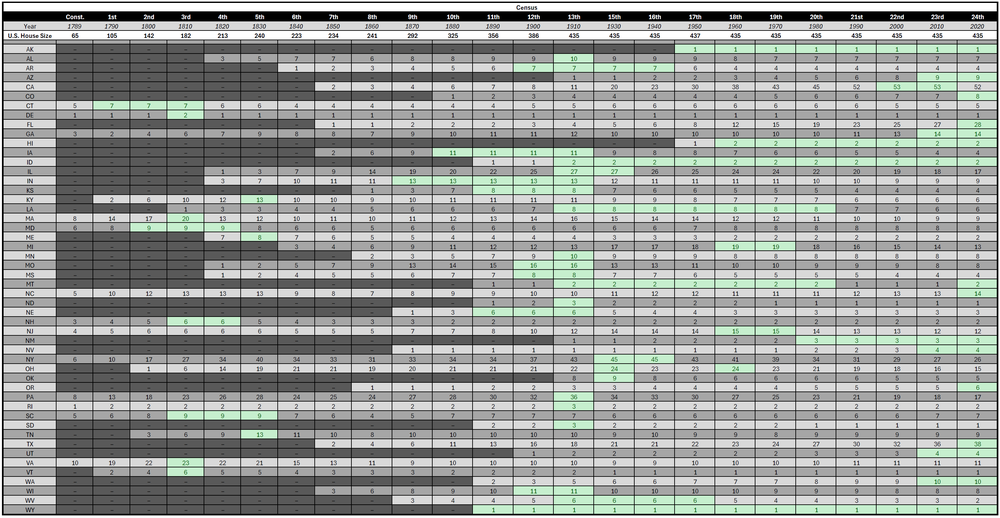

Congressional Apportionment - 1789 to 2020

The chart below shows congressional apportionment by state since 1789. Years in green denote the largest number of seats a state has received.